One of the five most valuable canyons—for just three to four percent of total electricity production

A battle is currently underway to preserve the natural values of the Komarnica Canyon, which the Electric Power Company of Montenegro (EPCG) plans to turn into an artificial reservoir similar to Piva. The outcome remains uncertain. EPCG promotes the project as a major capital investment that, they claim, will bring revenue to Montenegro once the dam is built, and turn the municipality of Šavnik into a leading tourist destination. On the other side, experts and environmental defenders warn that the people of Šavnik and Montenegro stand to lose much more than they would gain.

Dobrica Mitrović

Dobrica MitrovićThe Problem with the Komarnica HPP Project

It’s not the first time an energy project that’s not in the public interest has been promoted in Montenegro. We are well aware of how small hydropower plants (SHPs) were pushed as the perfect model for electricity generation, how EPCG and the Government of Montenegro trapped some of our rivers in pipes, and how they eventually abandoned further SHP construction after public pressure and significant damage. Now, EPCG and the Ministry of Capital Investments are promoting the Komarnica HPP project—as if it will save Montenegro and make it an energy-independent country living off electricity exports.

This outrageously expensive experiment, which would contribute only three to four percent of Montenegro’s total energy production, is already outdated. Similar projects are no longer pursued in many developed countries. For significantly less money, EPCG could obtain the needed energy by investing in reliable systems that rely on solar or wind power. Such carefully designed, nature-sensitive projects could generate even more electricity for Montenegro with far less environmental pressure.

It seems the key reason EPCG is pushing this economically and energetically inefficient project is that outdated hydropower strategy is the only path they know. The EPCG leadership either cannot adapt to modern needs or lacks the capacity to learn and develop contemporary, far more efficient energy projects that benefit both people and the planet. Numerous countries in northern and western Europe – with far fewer sunny days – are transitioning their energy production to solar. Outdated energy technologies are often marketed to developing countries like ours, backed by the flawed reasoning of overconfident engineers who claim, for some mysterious reason, that solar power can’t thrive in Montenegro, and that Komarnica is a “capital” project. But technology is advancing daily. We no longer have to choose between untouched nature and energy. We can—and have the right to—have both!

If EPCG truly wants to create an energy-independent Montenegro and turn it into an electricity exporter, why didn’t it build the Krnovo and Možura wind farms itself? These projects cost less and produce more electricity than the planned Komarnica HPP, and were simpler and more profitable. Instead of building them, EPCG gave them to private investors.

EPCG actually sees the Komarnica project as an experiment. This is confirmed by the fact that upstream from the proposed dam site there is a known and documented seismic fault—a 1.5 km long sinkhole—whose impact remains unaddressed. It’s still unknown where the enormous volume of water flowing through this sinkhole will resurface.

Dejan Lazarević

Dejan LazarevićThe Environmental Impact Assessment for Komarnica HPP heavily emphasises the supposed tourism potential of the reservoir, citing the number of tourists who visit Plužine. However, the tourists who stay overnight in Plužine don’t come for the reservoir—they come for the untouched Tara Canyon, the vast Piva mountains, and Durmitor. A reservoir that looks like any other in Europe is unappealing to tourists, while wild canyons inspire awe.

Montenegro is globally recognised for the Nevidio Canyon. Just for this part of Komarnica, at least 3,000 people visit Montenegro every year. Komarnica lies in a zone with a basic seismic intensity of 7 on the Mercali scale, and the planned Komarnica HPP would lead to almost daily seismic activity, which would also affect Nevidio. It will be hard to attract canyon and wilderness enthusiasts to Nevidio if the ground trembles due to the reservoir, and rocks fall from great heights—where even a walnut-sized rockfall can pose a serious risk to life.

The construction of the Komarnica HPP would not only destroy this canyon or cause the extinction of one of the richest habitats for endemic and other plant and animal species—it would also erase an entire concept of sustainable, healthy tourism based on canyoning.

Dejan Lazarević

Dejan LazarevićThe True Values of the Komarnica Canyon

Why is it important to preserve Komarnica from a biodiversity perspective? Some claim that today Komarnica is completely unusable for humans, that as a wild river and canyon it serves no purpose and offers nothing. However, canyons must not be seen as vertical wastelands, with high rocky walls shaped by the river over millions of years, where nothing lives. The truth is quite the opposite!

“River canyons are extremely complex mosaics of micro-ecosystems on steep slopes, with great diversity of ecological factors and a high degree of isolation of individuals, populations, species, and communities. This leads to the formation of narrowly distributed (endemic) biological systems. Most importantly, canyons allow for individuals and populations to move rapidly between ecosystems within this small space, which is a large ecological mosaic, in response to changes in climate conditions. This enables them to survive extremely unfavorable conditions.

In the ecological mosaic of canyon ecosystems, even under today’s macroclimatic conditions, both thermophilic (species from the interglacial periods) and cold-loving species find refuge. Thus, canyons such as Komarnica are by far the richest centers of endemic and relict populations, species, and ecological communities.

The Komarnica Canyon was shaped by nature over a long history of about 30 million years. Along with light, heat, and wind, the Komarnica also shaped the canyon’s living systems, imprinting them with its unique signature. The percentage of endemic species or populations in the rock crevices of canyons in the Drina basin (Komarnica, Piva, Tara) reaches up to 50%, which is the strongest confirmation of their relict (once widespread, now rare) and refugial (shelter) character of their communities and ecosystems as a whole,” emphasized professors Radomir Lakušić and Sulejman Redžić in a 1989 paper. Their work builds on their own and earlier research by the exceptional Piva and Balkan botanist Vilotije Blečić, whose house was near the Komarnica.

Habitats such as Komarnica, Morača, Tara, and the former Piva hold a special and crucial value among ecosystems because they serve as sanctuaries for plant and animal species during times of climate crisis. Canyons were the very places from which life began to spread across Europe again after the last Ice Age! Today, these habitats are called biodiversity hotspots, teeming with endemic, rare, endangered, and relict species. In the Komarnica Canyon, various rare and unique species still live today—some of which date back to pre-glacial times—and new species have evolved in these canyons, some of which are now found nowhere else in the world. One such species is the Piva bellflower (Campanula pivae), which still survives in Komarnica after losing its habitat in the Piva Canyon when it was flooded. Blečić gave this plant its name, pivae. Other species also carry the names pivae, durmitorae, and even komarnicae! The works of Blečić, and later Lakušić and Redžić, describing Komarnica, are full of words like “magnificent” and “natural gems,” referring to the canyon’s endemism rate, continuously highlighting the value and richness of species and plant communities that have survived thanks to the canyon.

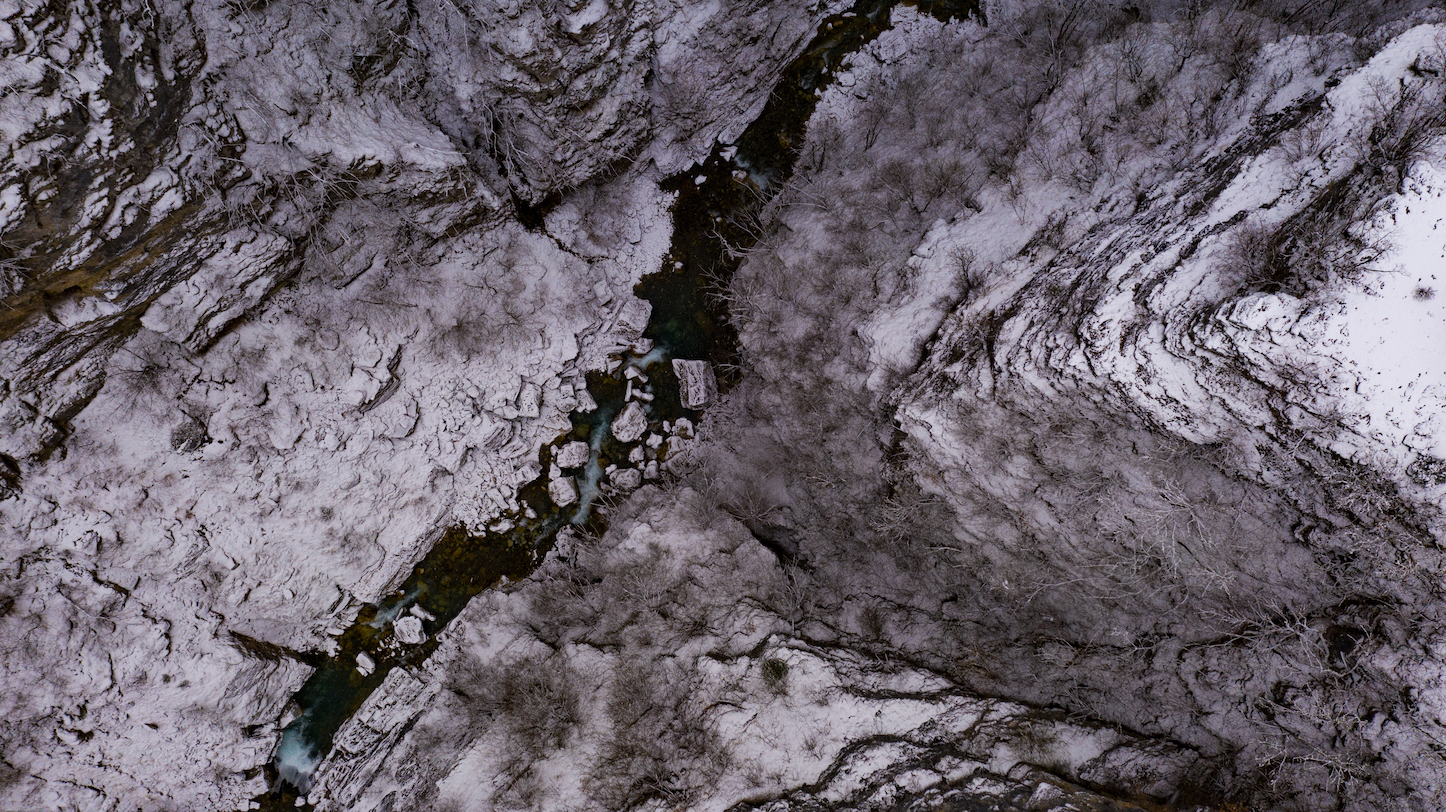

Just a look at the Komarnica Canyon reveals a unique wild landscape, where towering pines jut out from the rock, dense forests of linden and maple cover the terraces of the canyon, the river shimmers blue, and steep cliffs are home to rare species growing right on the stone…

According to experts, the Komarnica Canyon also holds enormous speleological potential, with a large number, morphological diversity, and biological richness of caves and pits. These caves are teeming with tiny endemic animals and bats. All bat species are protected in Montenegro. The canyon is also a refuge for otters, chamois, golden eagles, and dozens of other species of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and hundreds of less “charismatic” insects and other invertebrates. In this untouched area, they find a haven while humans continue to exploit accessible forests, rivers, and meadows in the mountains without consideration.

The unique plant communities that live and survive only on cliffs and scree – giving the canyon its distinctive appearance – are highly important natural systems, rich in endemic, rare, and endangered species. They would be most at risk from dam construction, as most of them would be submerged.

For aquatic and semi-aquatic species, total extinction would be a real threat – especially for those remnants of once-large populations that lived in the Piva River basin and survived only because they continued life in the Komarnica. Not to mention other species that people often deem valueless simply because they are not charismatic – yet these very species are essential to maintaining the health of nature, and therefore, of humans.

An area is only as healthy as its forests, rivers, and meadows are in balance, and their health is reflected in the number of plant and animal species that have shaped these systems for millions of years—and which still depend on them today. Many species that live in the Komarnica River will not be able to flee the canyon and start life elsewhere. Everything mentioned here is just a fragment of the real picture of Komarnica’s nature, which, in truth, we still know little about—because this expanse remains, for the most part, unexplored. And yet, despite how little we know, it has been enough for certain parts of Komarnica to be declared protected areas on both local and European levels.

One part of Komarnica was declared a protected area—a nature park—together with Dragišnica in 2017. The former canyons of the Piva and Komarnica rivers were declared a natural monument in 1969, and the Komarnica Canyon has been nominated as an Emerald Site, which means it is recognised for its high biodiversity. According to the European Union’s criteria, parts of Komarnica should be designated as Natura 2000 habitats.

The Komarnica Canyon is part of the key biodiversity area of Durmitor. Even UNESCO experts have recognised the canyon’s high value, and out of the entire Durmitor region, they proposed that a large portion of Komarnica be included in Durmitor National Park and added to the UNESCO World Heritage list. However, the municipality of Šavnik rejected the proposal.

This is not the first time that in Montenegro an area is declared valuable and protected one year, only to have projects planned in the following years that completely erase those values and render their protection meaningless.

“Canyons are not only geomorphological phenomena but highly specific geo-biocoenoses, where physical, chemical, and biological systems have been uniquely integrated through the long revolution of life, from the uplift of the Dinarides to the present day. The plant communities of canyons, made up of endemic biological systems from the periods before, during, and after the ice ages, are the most precious living documents of the evolution of life – and they deserve special attention in the organization of nature protection.” — This was written back in 1972 by Radomir Lakušić, one of the greatest Balkan botanists.

Most of the data on Komarnica was collected decades ago, and even back then, research recognised the canyon’s high value. On the other hand, many canyons in Europe were flooded in the past, which is why the canyons of Komarnica, Tara, and Morača now have immeasurable value for all of Europe – and the world.

Dejan Lazarević

Dejan LazarevićHydropower Plant Komarnica and the Climate Crisis

The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR5, 2014) warns that the Mediterranean region is extremely vulnerable to climate change and will in the future face multiple challenges and systemic disruptions due to climate change, noting that some of the expected disturbances to climate parameters in the Western Balkans are above the global average—such as the increase in average air temperature.

That climate change is already being felt here can be seen from the example of 2017: the Piva and Perućica hydropower plants produced half as much electricity due to significantly lower-than-usual rainfall, as well as poor water management in Montenegro. Numerous studies show that the intensity of climate change is certain to increase, which is yet another reason why hydropower is no longer a reliable energy source, and hydropower facilities can no longer serve as “batteries” like they once did.

At the same time, because of their unique characteristics and the services they provide – ecological, social, and economic – biodiverse and well-preserved areas contribute to the adaptation of both people and nature to new climate conditions, help mitigate climate change, and represent “nature-based solutions” in the fight against the climate crisis.

Andrijana Mićanović

Andrijana MićanovićThe need for electricity is real, but available green and sustainable solutions are being completely ignored

We fully agree that Montenegro should produce electricity, and we have nothing against EPCG’s (Montenegro’s Electric Power Company) intention to increase electricity production and earn large profits from its export. However, with the money planned for this ecocide investment, we could choose new, modern energy solutions instead of staying stuck in the past by pushing hydropower.

In the 21st century, when technology has advanced so much and when experts from leading energy-producing countries are offering solutions on a silver platter, we believe it is reckless to sacrifice such a valuable canyon for just three or four percent of our energy production. The canyon, the water, and what they build together are irreplaceable. A lost canyon cannot be restored, while that small percentage of energy can be obtained in other ways. The problem is that these alternatives require a bit more effort, more attention and planning – they require stepping out of the comfort zone EPCG has long enjoyed. The problem is also that, as a society, we are used to taking the beaten path, the seemingly easier way, and we resist anything new and modern because it demands more work, learning, and thinking.

After the closure of KAP (the Aluminum Plant), EPCG produces not only enough electricity for the domestic market but also manages to export a significant surplus, thus generating large profits. Therefore, Montenegro and its current and future citizens will not be left without electricity if Komarnica is not built – but they will be left without one of the most beautiful canyons in Europe.

The total construction costs of the Komarnica hydropower plant, which is planned to last at least seven years (and according to European experts, even more than 10 years), are significantly underestimated because they are based on incomplete documentation. Moreover, the investment cost estimates were made in 2020, before the sharp rise in construction and other material prices. But even if we accept the estimate of 260–290 million euros as realistic, that same amount could, in a much shorter time, be used to build solar power plants with a total capacity of 400 MW—since the construction of one megawatt costs about 700,000 euros. According to other calculations, solar panels covering about 1.5 km² would produce the same amount of electricity as the Komarnica plant. Alternatively, the same investment could be used to build wind farms with a total capacity of 187 MW, where the investment per megawatt is around 1.5 million euros—twice as much as for solar—but because wind turbines can produce twice as much electricity over the year compared to Komarnica, this investment would still be far more profitable.

Investing in outdated equipment to fix losses in the grid—which are currently twice the output of the Komarnica plant and whose reconstruction CEDIS (Montenegro’s electricity distribution system operator) plans to launch by 2024—would also significantly reduce energy deficits.

All these greener and more sustainable options are available to Montenegro now, which is why even considering the destruction of one of the five most valuable canyons in Europe is reckless. Investments in greener, modern energy strategies would be financially supported by various large European and other international funds, which no longer finance problematic, outdated hydropower projects.

Montenegrin Ecologists Society